Columbia Portland Cement

Though the rolling hills of southeast Ohio are mostly quiet now, for much of the 20th century they echoed with the sounds of booming mine operations, blasting coal and limestone out of the ground. One such mine operated by the Pittsburgh Plate and Glass Company, or PPG, was located south of the city of Zanesville and crushed limestone. There was ample supply - in 1921, PPG took core samples from around the area and found a shale deposit that would supply the plant for 125 years. To take advantage of the of the byproducts of the plant, PPG announced in 1922 that it would build a $2 million dollar cement plant on the site, including a powerhouse, office building, laboratory, machine shops, and worker homes. The plant would operate two wet kilns, as well as six 80 ft. high silos for storage.

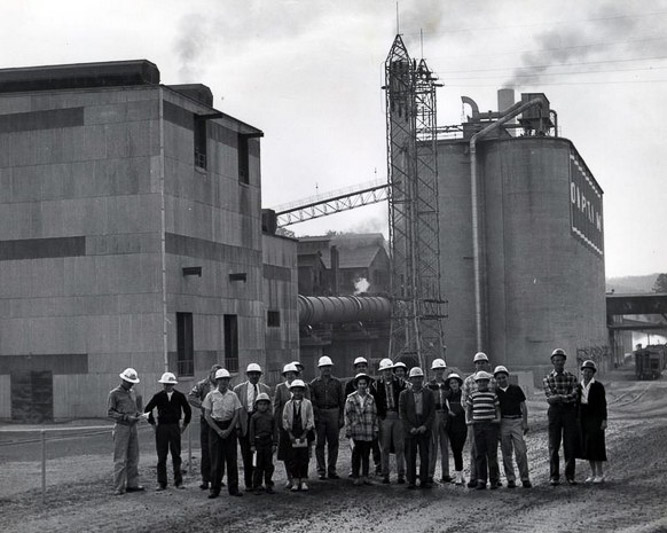

The first unit of the plant was finished in August of 1924, producing 2,500 barrels of cement a day. Sales of “Columbia” brand cement were brisk, and a year later the company began construction on a second unit that would bring capacity up to 5,000 barrels a day. Though the market for cement fluctuated during the Great Depression and the Second World War, demand increased in the postwar years.

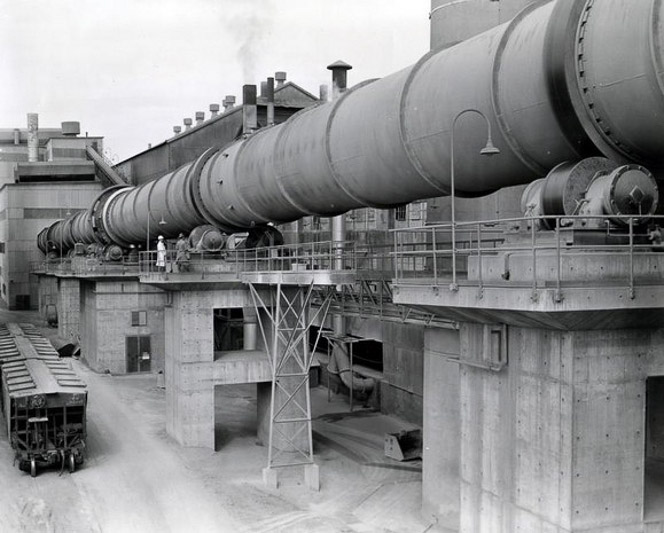

In June of 1955, the Columbia Cement division of PPG announced it was expanding the plant to double capacity to up to 11,000 barrels a day. New equipment included an automated 450-foot rotary kiln and grinding system, as well as improvements to the rest of the plant. Limestone was mined from the hills surrounding the plant, creating a huge network of underground tunnels linked by conveyer belts. In 1963, the plant was modernized again, with the installation of a new 450-foot kiln, loading facilities, and an underground raw materials storage building.

At one point the Columbia Portland plant was the largest in the state, and one of the larger employers of the surrounding area. However, in 1973, PPG sold its Columbia Cement subsidiary to Filtrol Corp., as part of an effort to shed non-essential businesses. The plant went through several owners in quick succession, as Filtrol was bought by U.S. Filter in 1978, which itself was bought by Ashland Oil in 1981. Ashland operated the mine and plant for three years before laying off many employees in 1984, and put the plant up for sale.

When Ashland Oil sold the plant in 1984 to the Columbia Portland Cement Co., the new company ran into problems with the union representing the plant workers. Soon after purchasing the plant, Columbia Portland terminated the existing collective bargaining agreement with the union and began negotiating a new one that cut some benefits and changed the grievance process. After talks broke down during the spring of 1985, the union voted to go on strike in May. Mine supervisors found that on their way out workers had sabotaged some of the equipment. Though the strike was called off, a second strike a few weeks later followed, which lasted through 1988.

Columbia Portland later became the Midwest Portland Cement Co., which filed for Chapter 7 bankruptcy in 1993 and shut the plant down. Though there are few details about this time, it appears that reopening the plant was not an option, as the EPA stepped in and began a major cleanup of the plant site and surrounding area that concluded in 1998. During or shortly after this time, large parts of the plant were demolished, including the kilns and storage warehouses.

The plant has sat vacant ever since, slowly deteriorating. In recent years emergency services and local military units have used the plant for training and live fire exercises. Soldiers from the Army 477th Military Police practiced building clearing in a 2007 exercise, and the Sheriff department used it for SWAT team deployments. Most recently it was used by a local fire department to train for building rescues.

In 2009, the plant was sold to Schmack BioEnergy, which built an alternative energy facility on the north side of the property. Though there don’t appear to be any immediate plans to tear down the cement plant, much of the area around it has been declared off limits by the Ohio EPA after large sink holes started to develop near homes northeast of the plant. Investigators found that the homes had been built over parts of the plant’s limestone mine that insufficiently reinforced, and starting to cave in. As of April 2014, officials are debating a mandatory evacuation of several nearby homes.