Continental Motors / Aluminum Plant

The early years of the auto industry were extremely competitive, as hundreds of carmakers entered the market, all looking to carve out a niche. Marquee names like Peerless and Stutz fought for a share of the luxury car business, while Dodge, Studebaker, Hudson, Graham, and dozens of others jostled for space in the mid and low-price market. But for all of their differences in styles, amenities, and prices, all of these companies and more had one thing in common: An engine made by Continental Motors under the hood.

Continental Motors can trace its roots back to 1903, when engineer Ross Judson presented a 2-cylinder engine at the Chicago Auto Show. As orders for the engine came in, the company incorporated as Continental Motors, and built a plant in Muskegon, MI in 1905. Continental's first major order for 100 engines came from Studebaker in 1906. A year later Studebaker needed 1,000 engines, and by 1911, Hudson was asking for 10,000 engines.

In order to be closer to the plants of their customers, Continental began construction on a large plant along Jefferson Avenue on the east side of Detroit in 1911. The two-story factory designed by Albert Khan was finished in 1912, with a capacity of 18,000 to 22,000 engines per year. Overlooking the plant and its separate two-story office building was the iconic smokestack with CONTINENTAL written down its side, with a 1,000 horsepower plant underneath.

Continental Motors dominated the automobile engine market through the 1910's and 20's, supplying motors to over 120 manufacturers in Detroit and around the country. In 1929, the company began building aircraft engines, and became a major supplier for small aircraft. Despite its use in so many brands, Continental remained a relatively unknown name to the consumer. When the company started building cars under the Continental name in the early 1930's they were poorly received by the public, and production ended after just a few years.

The Great Depression wiped out many of the smaller automakers, nearly taking Continental with it. The aircraft engine part of the business kept the company afloat until the onset of the Second World War.

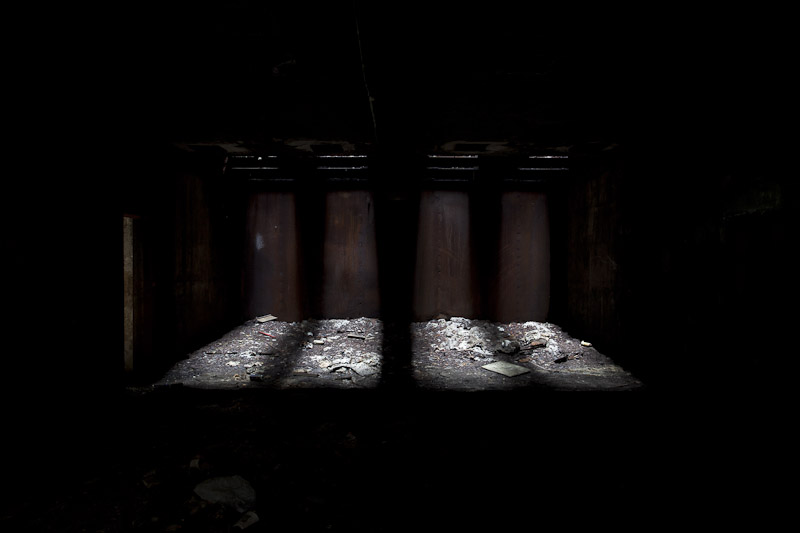

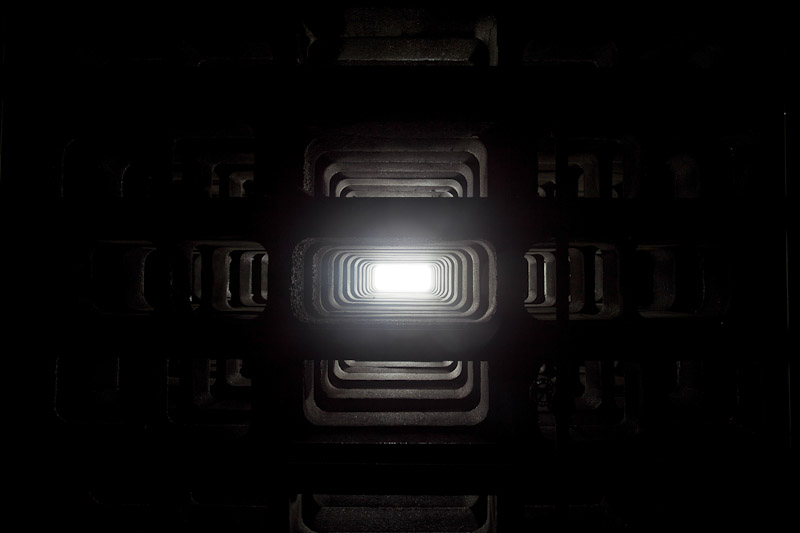

In 1939 the plant was converted over to build tank engines and engine parts. To test the engines before they were put into use, concrete testing cells were added onto the north side of the plant in 1942. Control rooms with blast-proof glass and thick concrete chambers allowed engineers to mount the engines and run them up to full power.

In the post-war years, the independent auto market shrank, decreasing demand for Continental engines. Anticipating reduced output, Continental mothballed part of the plant, and used the rest as a warehouse.

However, in 1945 a new automaker appeared on the scene, ready to take advantage of the pent-up demand for cars. Kaiser-Frazer was a joint venture between Henry J. Kaiser, a ship builder, and Joseph W. Frazer, who had been an executive at Chrysler. While other automakers struggled to convert back to civilian production, Kaiser-Frazer quickly rolled out a new design, and contracted with Continental to make the engines. Kaiser-Frazer engines began rolling off the Continental Motors-Detroit assembly line in November of 1946, and in early 1947, K-F leased the Jefferson Avenue plant from Continental. The Detroit Engine Division of Kaiser-Frazer Corporation employed 1,200 workers, and by August of 1947 was producing over 12,000 engines a month.

Though initially successful, Kaiser-Frazer foundered as the major automakers brought new products to market, and auto engine production was moved to other facilities in 1949. Part of the Detroit Engine Division plant was cleared out in 1951 and retooled for defense work, including motors for training planes and helicopters. Kaiser-Frazer bought the plant outright from Continental in late 1951, but the Korean War ended in 1953 just as military production was ramping up. When Kaiser-Frazer merged with Willys-Overland in 1953, most engine production was moved down to the Jeep factory in Toledo, OH. The Jefferson plant closed in 1955, and most of the tooling was sent to Argentina, where Kaiser was involved in a joint venture to produce cars.

Most of the plant had been demolished by 1961, aside from the power plant, a foundry building, and the test cells. Most of the land close to Jefferson was cleared, and in 1976 a new postal facility and an office for the Michigan Department of Social Services were built.

The plant’s last occupant was a metal smelting and recycling company called Continental Aluminum, which was formed in 1979. There was no relationship between this new company and Continental Motors, which had been acquired by Teledyne Incorporated in 1969. Continental Aluminum used only the foundry part of the plant to recycle aluminum, a process that is highly toxic. After numerous environmental complaints and fines, the company moved to a new factory out in the suburbs in 1998, abandoning the Jefferson Avenue plant.

Scrappers began eating away at the warehouse in 2006. The foundry was demolished in 2008, leaving only the test cells and the what’s left of the power plant. The water tower disappeared in 2011, taken down by scrappers. The rest of the plant was demolished in 2022.